Mermaids, Selkies, and Motherhood

Edge-dwelling, decision-making, and navigating the human experience through ancient archetypes

The Mermaid of the Fjord

A prequel to the lament of An Mhaighdean Mhara—the lament of the mermaid

Mary slips through the moonbeams cast on fine sand and slides towards shore. The fairy otherworld is visible as waves curl back over rocks,

anemones and starfish hold fast in the suck of the undertow.

The sea fairies are tucked away for the night, the brightly colored headdresses and adornments only visible to those who know where to look.

Waving and welcoming, Sea wraps her hands around Mary’s ankles and tugs,

Not today, Sea.

Nighttime shadows cast spells and Mary clasps her cloak around her neck,

the edges of today and yesterday are hazy and dark – and the Sea invites Mary to another time.

weaving through kelp forests,

napping on sun-warmed rocks,

throwing her head back to bark at the eternity of sky,

dancing for the moon with her sisters.

Maybe today, Sea.

Glancing back at the coast, the grasses sway in a gentle breeze and hide the eggs of puffins in their clutches and clumps. Parents tend to their nests, keeping with the ancient tradition and culture of the cliffs.

With each wave, Mary’s feet bury deeper in the sand, and she stands rooted between two worlds. She wiggles her toes and imagines being buried in the wet sand if she stands here too long.

For edges are meant to be treated with care, and we’re often visitors there,

A special few are edge-dwellers, adapted to survive in a constant state of transition,

but to most, to stand on the edge for too long is to be buried by the clash of two worlds—neither of one nor the other. And a choice has to be made.

As she sinks deeper, her two legs become a trunk, and she can almost remember what it was like to be bound within seal skin:

the freedom of that simple constraint,

the comfort of the skin she wore before.

She knew she had to take a step to get out of this in-between world–for to stay rooted here was to sink.

As the wet sand pulled her down, she ventured: Today, sea?

And the Sea reached for her waist with a swell and pulled her down into the otherworld where the fairies were waiting,

roused from their slumber by a moment of doubt, flapping its wings

and causing a hurricane.

Wiggling out and up from corners and nooks,

they danced with the Sea to a cacophony of rolling rocks and the prickly static of underwater noise.

We’ve got her back, Mary of the Sea,

To make a choice is the price to be free.

Flippers, whiskers, and a bit of kelp for hair,

her song of freedom howled to the salty air.

The fairies tugged her into her skin as the moon dipped towards the horizon and danced on the water.

Mary woke in a cave surrounded by the bones of fish.

She knew that Sea kept time in swells and surges, so she didn’t have to,

and the tide hid secrets, so she didn’t have to.

In the distance, she sees two familiar figures walking the shore,

with a bellow, she hoists herself into the water and starts swimming.

Cautiously, the tides carry her towards the children.

The girl waves frantically

and as two worlds merge, Mary can just make out

a small wooden brush clutched between the child’s small webbed fingers.

Like many children, I was deeply shaped by the story of the selkie, especially The Seal Maiden by Karan Kasey & Friends. My father is from Northern Ireland and moved to the United States during the tail end of the worst of The Troubles, so my sister and I grew up with an American and complicated Irish identity. For me, and likely for most diaspora generations, the stories–whether through folktales, family histories, or music–formed a bridge between these two worlds.

Even beyond the cultural ties, the story of the selkie has always intrigued me. As a child who loved the ocean, I saw the selkie as a fantastical sea creature, shape-shifter, and a magical heroine who eventually frees herself from the prison of life on land. Now as I make my way through my early 30s, I have begun to relate to her secret inner world more—her world as a mother, as a woman straddling two seemingly incompatible identities, and as someone who has to make hard choices in order to live a life more true to herself. And as I get older and begin to realize everything isn’t as black and white as it seemed in my younger years, I am also starting to appreciate the tender ambiguity of the ending. This story does not always have the fairy-tale ending I once thought.

The Story of the Selkie: the woman between two worlds

There are many iterations of the story of the selkies, or seal people, but a common version tells of a group of seal women that come ashore to dance in the moonlight on the beach. Leaving their skins on nearby rocks, they trade their flippers for feet. As the sun rises, they don their skins and return to sea, but one skin is missing. A fisherman has come across the women dancing along the shoreline and steals the skin of a beautiful selkie. The skin is a selkie’s power and gives her the ability to tread the edge between life on land and life in the sea. Without her skin, this selkie is forced to stay human and marry him. He hides her skins away, and she mournfully lives a life on land, having his children and pining for the life she lost. She can only return to the ocean once her children find the skin hidden away and return it to her.

In Gaelic, mermaids and selkies are often interchangeable and referred to as ‘maidens of the sea.’ Many personal accounts of Irish stories (collected and available on dúchas.ie) tell of a mermaid who met a fisherman. The fisherman, taken by her beauty, steals something of hers so she’s unable to return to sea. This item ranges from a cloak, cap, wand, or magical mantle across many different accounts. She was forced to marry him, and while they had several children together, she never laughed while on land. One day, she recovered her item and was able to return victorious to the sea. She was said to be laughing as she fled.

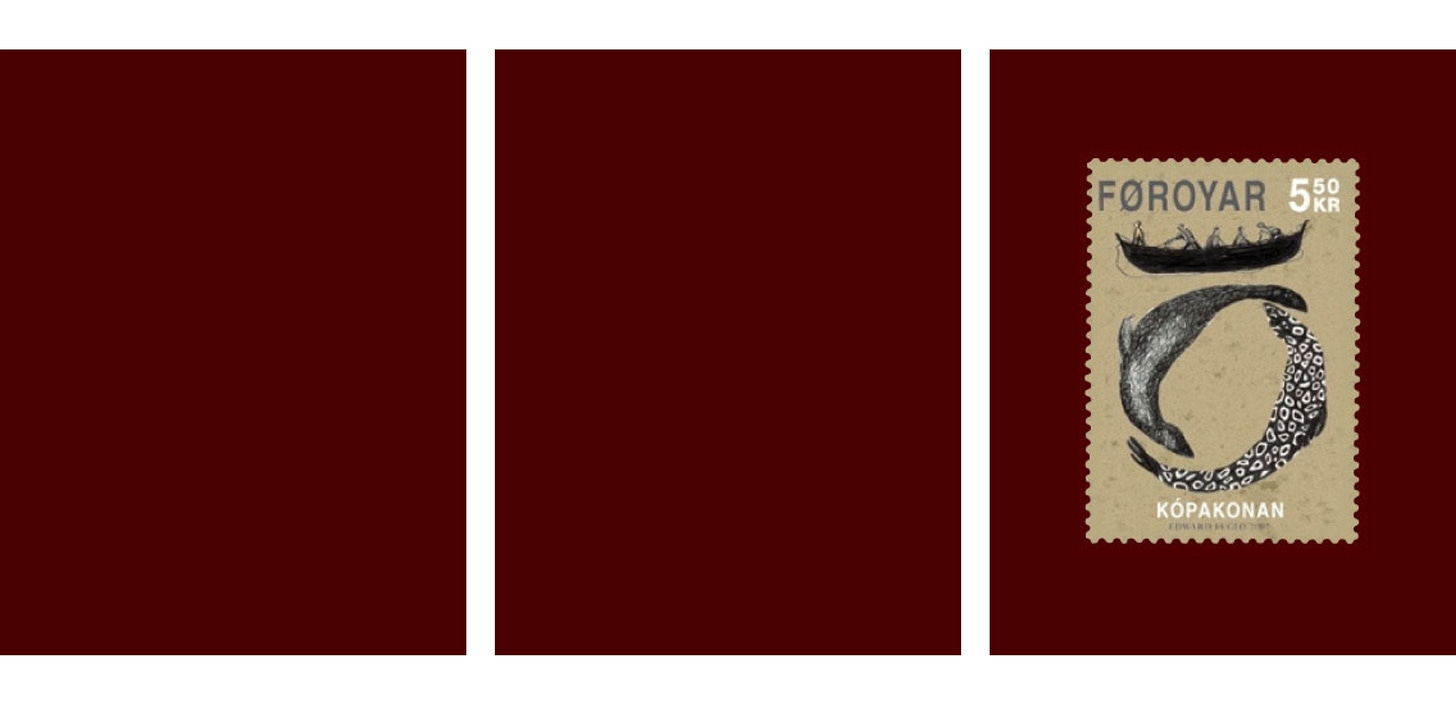

Her story is not uniquely Irish, and she appears in the folktales of many cultures, from Scotland to Scandinavia. We see the selkie archetype in the story of the sea elves of Iceland, as recorded by poet (and alleged sorcerer) Jón lærði Guðmundsson in the mid-1600s. Or as the Kópakonan, seal woman, of the Faroe Islands, where she is memorialized as a statue stuck in this in-between state, her seal skin held up around her waist as she solemnly gazes to shore, eternally mid-transformation. The Faroese stamp collection, released by Edward Fuglø in 2007, beautifully illustrates the selkie story and its haunting ending. Many find modern meaning in her story as we grapple with our devastating effects on the natural world. They see her story as a warning against our determination to exert power over nature.

An Mhaighdean Mhara

But today, we visit the selkie of the well-known Irish lament, An Mhaighdean Mhara, which translates to ‘The Mermaid.’ In this lament, we are witnessing a tender and mournful moment between our mermaid Mary and her daughter. Mary has swum far to visit her children and is tired. We meet her as the mermaid who chose to return to the sea, and she sits brushing her daughter’s hair as they talk. They don’t say much, and it can be difficult to decipher their conversation as there are a few different translations and interpretations–but the tender aching of both mother and children is felt in the space between words and through the undulating melody that mimics the hypnotic lull of ocean swells:

You seem to have pined away and lost your good spirits

The snow is deep at the mouth of the ford:

Your yellow coloured hair and your neat mouth;

Here come I, Mary Heeney, having swum the ErneSweet mother, said Fair Maura

Beneath the bank of the stony beach and the mouth of the strand,

My dear mother is a mermaid,

Here come I, Mary Heeney, having swum the ErneI am tired and will be until the day.

My girl Maura and my fair Patrick

On the surface of the waves and at the ford’s mouth.

Here come I, Mary Heeney, having swum the Erne

In my introductory poem, The Mermaid of the Fjord, I explore Mary’s choice to return to the sea as a prequel to the lament, and the poem ends as Mary is reunited with her children. Some see An Mhaighdean Mhara as a metaphor for death, the meeting of souls in the in-between of life and death. For me, An Mhaighdean Mhara represents a woman navigating motherhood and ultimately choosing to go back to her old life. As we sit with our selkie on the rocks of the fjord, I imagine she is struggling with the conflict between her two selves, pining for the identity she used to have as a selkie before children and mourning the mother identity she had on land, even though the latter was likely forced upon her. She has been transformed by motherhood, and so returning to her selkie self does not come without tension. She finds it difficult to reconcile the two into a merged life, and we glimpse this tension as she brushes her daughter’s hair during an unremarkable moment that becomes laden with significance. In this moment, she is able to dip a toe into both lives, even if they are merely shadows of her former lives.

To me, this moment in the fjord is her reconciled life in all its tragic and mournful beauty. Sometimes, reconciling two lives doesn’t mean everything turns out fairy-tale perfect. In this rendition, she doesn’t return to sea, laughing; she hovers near shore, existing in liminality so she can be both mermaid and mother. To her, holding two truths is painful, and that can be the beauty of life–having something to miss once it is sacrificed while allowing what you have now to be precious in its own way. In this light, the meeting is sorrowful but treasured. Our mermaid Mary is able to be true to herself while also being a mother in a way that makes sense to her, however painful.

Motherhood and the Selkie Archetype

To me, the selkie is a symbol of transformation and liminal spaces. She is a bridge between ocean life and life on land. Crossing and intermingling between the two, she leaves her mark on both. Sometimes interchangeable with mermaids, she sits in our minds as a magical shape-shifting figure of folklore and an archetype of the woman between two worlds. Throughout history, women have often held these mediating spaces: as midwives birthing new life and as death stewards ushering life onward (such as the keeners of Irish wake traditions). In most selkie stories and mermaid folktales, she is often entrapped by a man who forces her to dwell on land with him, but I imagine her untethered by these retellings, moving unsettled between two worlds so we never know which is her true identity: the one she was born into, or the self she embodies now.

As I swim further into my 30s, the prospect of motherhood is on my mind. Thinking about what the next decade holds, I can’t help but become paralyzed by the idea of giving up something of myself for an unknown. Thinking of myself as a mother someday feels unfamiliar and I am unsettled by the lack of clarity I have about what I’ll be like once I cross that threshold. Our current society is not supportive of this transition, and being able to hold onto two truths without great sacrifice is nearly impossible. What of myself would I leave behind if I stepped into the mother role? What parts of me will survive the transformation, and what parts of myself will need to be shed as I step into a new life? Will I eventually forget who I once was?

Maybe it will take a moment of recognition—finding a silky skin locked away in a closet or looking at a piece of me in my child—to stir up memories of who I once was. And in that moment, will I want to run backward? Will I be able to hold two versions of myself and live two lives at the same time, or will both become empty in that pursuit? Unlike our Selkie–and unlike many women around the world–I am fortunate enough to have the choice to cross this threshold or not.

I know I’m not alone in these questions–this is a timeless struggle and experience for women, whether we see it revealed in the folklore of centuries past or revisited today in our realities. We often explore history in a linear pattern—never-ending timelines of upward progress and innovation building off whatever came before. But it is curious to find treasures from previous eras that still resonate deeply today. Across geographic space and time, these stories remind us that our progress as humans is much more of a spiral upward. We can choose what we are carrying forward from the past and what we are losing along the way–the good and the bad.

The Power of Archetypes

For me, I find great relief in knowing that the issues I’m struggling with are just part of the human experience, something so quintessential–for better or worse–that it’s been immortalized into an archetype that shows up in stories of all ages and times. The stories and mythology of our ancestors are often windows to our collective human experience. They offer a cultural sandbox to work through our values, personal qualities, and societal priorities. And ultimately, I see them as a place to recognize that, often, these archetypes are born from deeply human realities that transcend geography, culture, or time.

In folklore throughout the ages, the ability to cross between worlds and tread the margins and edges is a privilege that carries weight and power, whether or not we appreciate it in our society today. Even in nature, intertidal species are some of the hardiest, most resilient, and adaptive species, able to thrive in a state of constant flux. That tidal zone is what brought life to land and, in folklore, allows our selkie to live with one foot in our world and one flipper in the sea. Maybe we find our power in this in-between state and refuse to reconcile the two because why should we? There is tender resilience and a strong hardiness in navigating contradictions.

In the end, we meet stories where we are at. They mix with our inner turmoil, and we search to make sense of the world by relating to them through our unique lens. The archetype of the selkie persists, and her story lives on because people can find something of their life in her story, whether it soothes or agitates or serves as a safe place to work out a dilemma. Engaging with stories in this way keeps them alive. It is not a passive retelling but an unraveling–getting to know ourselves and nature better through the stories we relate to and continue to tell.

Resources and offerings:

I first encountered the mermaid’s lament in my lessons with the wonderful Mary McLaughlin. She introduced me to the translation that I have provided in this piece, and to the údar, or story context, that accompanies this simple yet profound lament. She is a singer-songwriter who has spent decades researching and teaching not only Irish songs, but the traditions, stories, and historical contexts that they exist within.

The beautiful stamp images that I use throughout are a from the Faroese stamp collection. I also adapted one of the stamps to create the image of the dancing seals with the seal maiden.

The Dúchas Project is a magical resource where I found over 250 accounts of mermaid stories. It is a project to digitize Ireland’s National Folklore Collection (NFC) so that this material is not lost and can continue to grow.

I took creative liberties in switching ‘ford’ for ‘fjord’ in my interpretation.

“What Tessa said…”😍 AND never fear, you will be a terrific mother carrying all of your self with you forward! ❤️

Absolutely stunning weaving of poetry, storytelling, and reflection. <3